Silvia Avallone: Swimming to Elba

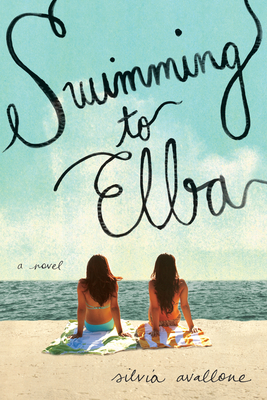

I first fell in love with the cover of the Hungarian edition of this novel. The English-version cover also captures the mood and atmosphere of the story and the two protagonists’ longing well, but I found the Hungarian cover even more evocative. I could spend hours watching the young girl on the seashore, with the steel factory behind her, gazing at Elba which is only a couple of kilometers away and thinking that if only she could get there, everything would be all right. And when I started reading, I liked the book just as much as I liked its cover.

The novel is set in Piombino, an Italian town renowned for its steel industry. The characters all live utterly bleak and hopeless lives: the girls either get married before the age of eighteen or prostitute themselves; the boys drop out of school at the age of sixteen and start working in the steel factory; and by the age of thirty, everyone becomes apathetic and doesn’t expect anything from life anymore.

In Piombino everything happens too early: at the beginning of the novel the protagonists, Anna and Francesca, two thirteen-year old girls on the verge of becoming women, still play childish games and spend their time innocently showing off their perfect teenage bodies to the idlers on the dirty beach and the fathers and uncles watching them from the nearby houses. Then a mere couple of months pass and the innocence is already gone – both from their minds and from their bodies.

Apart from learning what exactly happens to Anna and Francesca in less than a year, we also get acquainted with several people from the Stalingrad Street neighborhood: a wife who is planning to escape from her savage husband but finally reverts to medicine addiction; small-time and bigger-time criminals; violent and unreliable husbands; steel factory workers and shop assistants; and so on.

None of the characters has an enviable life, and when I started to read I felt suffocated by all the hopelessness emanating from the pages of the novel. Avallone depicts the bleak blocks of flats, the heat of the Piombino summer, the wives playing cards under the trees in the afternoons, or the steel factory dirt covering the skin of the men frighteningly well. And her descriptions make it clear from the very beginning: it’s almost pointless to dream about anything here, since the mere desire to get away is not enough – it takes a lot of work, guts and also luck, and this is a rare combination.

But after a while I became immune to the book. After a while I felt that Avallone tried to be too clever and she made special efforts to make me understand that she was indeed writing about terrible things. And I resent this. I don’t want a writer to tell me several times that the father beats his daughter – I get the point for the first time. And I don’t need to be told three times that the pasta prepared for dinner gets cold and sticky – I understand for the first time that this means that the family members don’t respect each other enough to appear at the table when dinner is ready, and that this is bad. Of course I may try to convince myself that all these brutal or simply bleak details are mentioned over and over again because this is how people live on Stalingrad Street, and beatings and cold pasta are their everyday reality – however, in spite of all its sociographic qualities, this is a novel, and I expect things to be a little more proportional in a work of fiction.

Especially since the author herself takes extra pains to emphasize that this is fiction. For instance, she directly states at the beginning of the book that it’s a work of fiction and that any kind of resemblance to real events or persons is unintentional (this, I guess, means that she supposes that her novel could be mistaken for a work of non-fiction). But what is more important, Avallone often writes in a forced, annoyingly „literary” way: she employs all kinds of deeply (?) symbolic motifs, and she writes sentences which might look just fine in any cheap collection of „wise” sayings but they don’t look good in a piece of literary fiction at all. (I have no exact quotes ready now, and anyway I read the novel in Hungarian, but I mean sentences roughly like these: „Reality always wins. Reality always takes what it deserves.” Oh, indeed.)

I assume this irritating cleverness and literariness arises from the inexperience of the author – this is her first novel. And anyway, what Avallone says is certainly important and meaningful, and her novel indeed shows me something of another world which I might not even think is there. What’s more, she manages to avoid the trap of a compulsory happy ending. However, Swimming to Elba doesn’t convince or fascinate me as a novel – and why should I not read and interpret it as a novel if it is one.

The novel is set in Piombino, an Italian town renowned for its steel industry. The characters all live utterly bleak and hopeless lives: the girls either get married before the age of eighteen or prostitute themselves; the boys drop out of school at the age of sixteen and start working in the steel factory; and by the age of thirty, everyone becomes apathetic and doesn’t expect anything from life anymore.

In Piombino everything happens too early: at the beginning of the novel the protagonists, Anna and Francesca, two thirteen-year old girls on the verge of becoming women, still play childish games and spend their time innocently showing off their perfect teenage bodies to the idlers on the dirty beach and the fathers and uncles watching them from the nearby houses. Then a mere couple of months pass and the innocence is already gone – both from their minds and from their bodies.

Apart from learning what exactly happens to Anna and Francesca in less than a year, we also get acquainted with several people from the Stalingrad Street neighborhood: a wife who is planning to escape from her savage husband but finally reverts to medicine addiction; small-time and bigger-time criminals; violent and unreliable husbands; steel factory workers and shop assistants; and so on.

None of the characters has an enviable life, and when I started to read I felt suffocated by all the hopelessness emanating from the pages of the novel. Avallone depicts the bleak blocks of flats, the heat of the Piombino summer, the wives playing cards under the trees in the afternoons, or the steel factory dirt covering the skin of the men frighteningly well. And her descriptions make it clear from the very beginning: it’s almost pointless to dream about anything here, since the mere desire to get away is not enough – it takes a lot of work, guts and also luck, and this is a rare combination.

But after a while I became immune to the book. After a while I felt that Avallone tried to be too clever and she made special efforts to make me understand that she was indeed writing about terrible things. And I resent this. I don’t want a writer to tell me several times that the father beats his daughter – I get the point for the first time. And I don’t need to be told three times that the pasta prepared for dinner gets cold and sticky – I understand for the first time that this means that the family members don’t respect each other enough to appear at the table when dinner is ready, and that this is bad. Of course I may try to convince myself that all these brutal or simply bleak details are mentioned over and over again because this is how people live on Stalingrad Street, and beatings and cold pasta are their everyday reality – however, in spite of all its sociographic qualities, this is a novel, and I expect things to be a little more proportional in a work of fiction.

Especially since the author herself takes extra pains to emphasize that this is fiction. For instance, she directly states at the beginning of the book that it’s a work of fiction and that any kind of resemblance to real events or persons is unintentional (this, I guess, means that she supposes that her novel could be mistaken for a work of non-fiction). But what is more important, Avallone often writes in a forced, annoyingly „literary” way: she employs all kinds of deeply (?) symbolic motifs, and she writes sentences which might look just fine in any cheap collection of „wise” sayings but they don’t look good in a piece of literary fiction at all. (I have no exact quotes ready now, and anyway I read the novel in Hungarian, but I mean sentences roughly like these: „Reality always wins. Reality always takes what it deserves.” Oh, indeed.)

I assume this irritating cleverness and literariness arises from the inexperience of the author – this is her first novel. And anyway, what Avallone says is certainly important and meaningful, and her novel indeed shows me something of another world which I might not even think is there. What’s more, she manages to avoid the trap of a compulsory happy ending. However, Swimming to Elba doesn’t convince or fascinate me as a novel – and why should I not read and interpret it as a novel if it is one.